Poetry Therapy: Towards an Uncommon Sense

A Brief History of Poetry Therapy

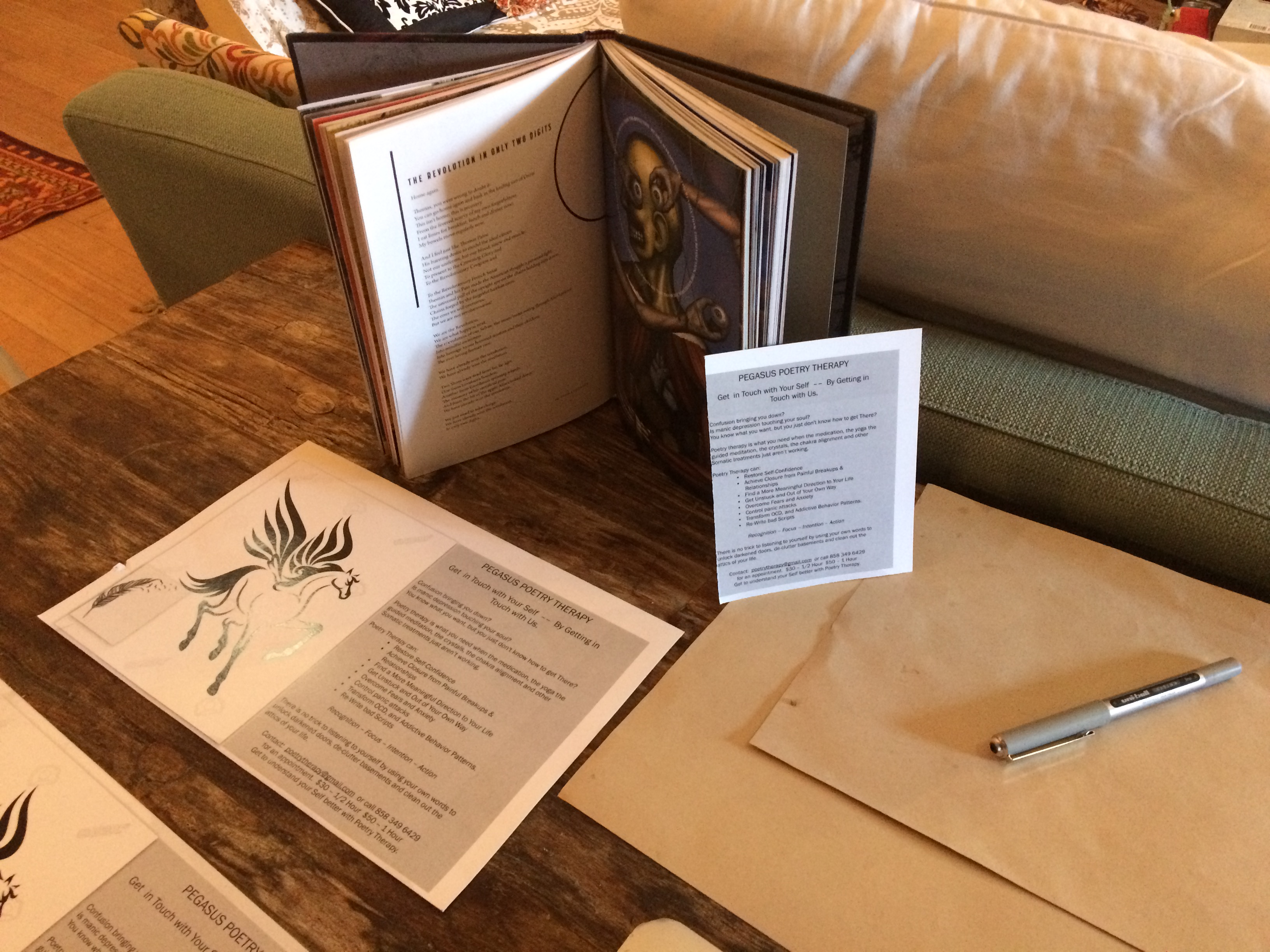

From the collection of poetry, philosophy and art TAKE A DEEP BREATH: Living With Uncertainty

by Igor Goldkind (Chameleon Publishing, 2021)

Poetry Therapy, or poetry which is used for healing and personal growth, can be traced back to primitive Man, who used religious rites in which shamans and witchdoctors chanted poetry for the well-being of the tribe or individual. It is documented that as far back as the fourth millennium B.C.E. in ancient Egypt, words were written on papyrus and then dissolved into a solution so that they could be physically ingested by the patient and take effect as quickly as possible.

The first poetry therapist of historic record was a Roman physician by the name of Soranus in the first century A.D., who prescribed tragedy for his manic patients and comedy for those who were depressed. It is not surprising that Apollo is the god of poetry as well as medicine, since medicine and the arts were historically entwined. For many centuries the link between poetry and medicine remained obscure. The poet John Milton wrote in 1671:

“Apt words have power to swage The tumours of a troubled mind And are as balm to festered wounds.” Pennsylvania Hospital, founded in 1751 by Benjamin Franklin and the first in the United States, employed many ancillary treatments for their mental patients, including reading, writing and the publishing of their work. Dr. Benjamin Rush, called the ‘Father of American Psychiatry’, introduced music and literature. The writing of poems was was encouraged, and the results were published in The Illuminator, their own newspaper.

On the battlefields of the American Civil War, Union field medic Walt Whitman would administer recitations of verse to fallen soldiers who were well beyond hope long before the use of morphine. He was later to pen the classic Leaves of Grass, the greatest celebration of humanity in the midst of its own despair. Pennsylvania Hospital employed this approach as early as the mid- 1700s.

In the early 1800s, Dr. Benjamin Rush also introduced poetry as a form of therapy to those being treated. In 1928, Eli Greifer, an inspired poet who was a lawyer and pharmacist by profession, began a campaign to show that a poem’s didactic message has healing power. He began offering poems to people as prescriptions, and eventually started “poem-therapy” groups at two hospitals with the support of psychiatrists Dr. Jack L. Leedy and Dr. Sam Spector. After Griefer’s death, Leedy and others continued to incorporate poetry into the therapeutic group process, eventually coming together to form the Association for Poetry Therapy (APT) in 1969.

Librarians also played a major role in the development of this therapeutic approach. Arleen Hynes was a hospital librarian who began reading stories and poems aloud, thus facilitating discussions on the material and its relevance to each individual in order to better reach out to those being treated and encourage healing. She eventually developed a training program for those interested in teaching poetry therapy.

In 1980, all the leaders in the field were invited to a meeting to formalize guidelines for training and certification. At that meeting, the National Association for Poetry Therapy (NAPT) was founded. As interest grew, books and articles were published to guide practitioners in the practice. Hynes and Mary Hynes-Berry co-authored the 1986 publication Bibliotherapy — The Interactive Process: A Handbook. More recently, Nicholas Mazza outlined a model for effective 188 poetry therapy, also discussing its clinical application, in Poetry Therapy: 189 Theory and Practice.

The Journal of Poetry Therapy, established in 1987 by the NAPT, remains the most comprehensive source of information on current theory, practice, and research. There is also a relationship between psychological healing and incantations, either repeated as a musical chant by the patient or recited by the attending medicine man. Of course, modern medicine and science consider the notion of magical incantations possessing healing or restorative powers as so much superstition.

But this, of course, begs the question that if recitations and incantations had no evidential result and no beneficial property then why would have nearly every human culture have adopted the method and repeated it for thousands of years? Surely if there was no value to vibrating the air with the sound of one’s breath, rising from the abdomen, pushed upwards by the lungs, shaped by the throat, mouth and tongue, with the added stimulation of associative meanings being understood cognitively by the patient’s mind, we would have given it and its sisters, singing and chanting, up aeons ago.

I am not advocating a supernatural or spiritual causation for the effectiveness of poetry as a healing agent, but rather the supra-natural mystical cause which is grounded first in human nature and cognition, and for which there maybe a myriad of imprecise explanations, none of which can fully explain why it works. Today, poetry therapy is practiced internationally by hundreds of professionals including poets, psychologists, psychiatrists, counselors, social workers, educators and librarians. The approach has been used successfully in a number of settings — schools, community centers, libraries, hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and correctional institutions, to name a few.

SO HOW DOES POETRY THERAPY WORK?

• Poetry is beneficial to the process of introspection, and can be used as a vehicle for the expression of emotions that might otherwise be difficult to express

• Poetry promotes self-reflection and exploration, increasing selfawareness and helping individuals make sense of their world.

• Poetry helps individuals redefine their situation by opening up new ways of perceiving reality.

• Poetry helps therapists gain deeper insight into those they are treating.

In general, poetry therapists are free to choose from any poems they believe offer therapeutic value, but most tend to follow general guidelines. Some poems commonly used in therapy are: The Journey by Mary Oliver Talking to Grief by Denise Levertov The Armful by Robert Frost I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud by William Wordsworth Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman Turtle Island by Gary Snyder as well as the poetry of Alan Watts, Allen Ginsberg and Antonin Artaud.

TECHNIQUES USED IN POETRY THERAPY

Different models of poetry therapy exist and are being refined all the time, but one the most popular is the model introduced by Nicholas Mazza. According to this model, poetry therapy involves three major components: Receptive/Prescriptive, Expressive/Creative, Symbolic/Ceremonial.

I. In the Receptive/Prescriptive component, the poet merely introduces the subject of how to focus on their own issue. The aim is to establish concentration and cognitive focus on the details, none which is revealed to the poet. Only when the poet feels confident that the subject is cognitively attuned to and non-verbally focused on the problem or issue of concern does he or she begins to ask suggestive questions as to how the subject feels, not thinks, about their issue. This provocation of tangible emotions usually comes in three distinct phases of emotional content. First is the predicament, when the subject becomes aware of the existence of the issue. This is a gateway phase, where anticipatory feelings are illicit and registered by the poet.

II. Then there is a further stage when anticipation of the issue has given way to the full experience of all the emotions, anxieties and fears related to the issue. This is usually overwhelming (or it wouldn’t be ‘an issue’ in the first place), and it is paramount that the poet guides the subject through distinct words to describe the layers of emotions experienced by the subject. The poet must ground the subject’s emotions in language. Language and the use of words is the key here, because emotions always come in complex clusters that make it difficult for both poet and subject to distinguish them and focus on the underlying causes.

“What kind of anger do you feel?”, “How would you describe your sadness?”, “How much shame do you feel? What would you compare it to?” This is a sophisticated method of word association, but rather than creating bridges between seemingly disparate words the goal is to drill down to the core emotions of the issue by refining the language, as led by the subject. Achieving exactitude of description is the task at hand. The poet makes careful notation of everything the subject says in regard to describing their emotions. It is important to keep them focused and not to succumb to intellectual distraction. Thoughts are illusions and often lies, whereas emotions are facts. Get the subject to correctly describe the facts of the matter. All meaning is metaphorical.

III. The final stage is waiting for an exit strategy. How do the feelings begin to recede? How does the issue move back into the background? What are the parting emotions? Is there anxiety about the leaving? Anticipation of an issue yet unresolved? Or is the issue impermeable, and subject to a rhythmic return? Again, the subject’s wording, their adjectives, adverbs and phrases are the material of the poem. At this point there is usually a short break to give time for the subject to recover from the emotional transitions and for the poet to briefly skim their notes and begin to focus on the flow of adjectives. It is preferable, if possible, to compose what amounts to a first draft, a flow of words which the poet can read back to the subject to confirm its accuracy.

At this first reading stage it is possible to start interjecting logical bridges between the emotional descriptors. This is the creative factor 194 unleashed. The poet, assisted by the subject, creates coherent sequences 195 between the emotional states. The poet suggests and the subject confirms or vetoes the phraseology, one line at a time. Now we arrive at a second draft which is the property of the subject. It is their poem. The preference is that the subject now reads the poem aloud and takes ownership of its content. The subject can redraft the poem a third time, or many more times, claiming it as their own. The poet has merely provided poesy prompts, the poem is the creation of the subject.

The expressive/creative component involves the use of creative writing — poetry, letters, and journal entries — for the purpose of assessment and treatment. The process of writing can be both cathartic and empowering, often freeing blocked emotions or buried memories and giving voice to one’s concerns and strengths. Some people may doubt their ability to write creatively, but therapists can offer support by explaining they do not have to use rhyme or a particular structure. Poets can also provide stem poems from which to work, or introduce sense poems for those who struggle with imagery. A poet might also share a poem with their subject and then ask them to select a line that touched them in some way, and then use that line to start their own poem. In groups, poems may be written individually or collaboratively.

Group members are sometimes given a single word, topic, or sentence stem and asked to respond to it spontaneously. The contributions of group members are compiled to create a single poem which can then be used to stimulate group discussion. The symbolic/ceremonial component involves the use of metaphors, storytelling and rituals as tools for effecting change. Metaphors, which are essentially symbols, can help individuals to explain complex emotions and experiences in a concise yet profound manner. Rituals may be particularly effective to help those who have experienced a loss or ending, such as a divorce or death of a loved one, to address their feelings around that event. Writing and then burning a letter to someone who died suddenly, for example, may be a helpful step in the process of accepting and coping with grief.

HOW CAN POETRY THERAPY HELP?

Poetry therapy has been used as part of the treatment approach for a number of concerns, including borderline personality, suicidal ideation, identity issues, perfectionism, and grief. Research shows the method is frequently a beneficial part of the treatment process. Several studies also support poetry therapy as one approach to the treatment of depression — it has been repeatedly shown to relieve depressive symptoms, improve self-esteem and self-understanding, and encourage the articulation of feelings. Researchers have also demonstrated poetry therapy’s ability to reduce anxiety and stress. Those experiencing post traumatic stress have also reported improved mental and emotional well-being as a result of poetry therapy. Some individuals who have survived trauma or abuse may have difficulty processing the experience cognitively and, as a result, suppress associated memories and emotions.

Through poetry therapy, many are able to integrate these feelings, reframe traumatic events, and develop a more positive outlook for the future. People experiencing addiction may find poetry therapy can help them explore their feelings regarding substance abuse, perceive drug use in a new light, and develop or strengthen coping skills. Poetry writing may also be a way for those with substance abuse issues to express their thoughts on treatment and behavioral change. Some studies have shown poetry therapy can be of benefit to people with schizophrenia, despite the linguistic and emotional deficits associated with the condition. Poetry writing may be a helpful method to describe mental experiences, and can allow therapists to better understand the thought processes of those they are treating.

Poetry therapy has also helped some individuals with schizophrenia to improve social functioning skills and foster more organized thought processes. It is important to note in many instances, especially in cases of moderate to severe mental health concerns, that poetry therapy is used in combination with another type of therapy and not as the sole approach to treatment.

TRAINING FOR POETRY THERAPISTS

Poetry therapists receive literary as well as clinical training to enable them to be able to select literature appropriate for the healing process. While there is no university program in poetry therapy, the International Federation for Biblio-Poetry Therapy (IFBPT), the independent credentialing body for the profession, has developed specific training requirements. Several studies support poetry therapy as one approach to the treatment of depression, as it has been repeatedly shown to relieve depressive symptoms, improve self-esteem and self-understanding, and encourage the expression of feelings.

However, the only qualitative measure of effective poetry therapy is in the poesy and the results. No accreditation can guarantee or substitute for the quality of cognitive empathy that is achieved during a successful session. Ultimately, there can be no real separation between the experience of the poet and the subject. This methodology provokes a meeting of mind in confrontation with universal truths. The poet is there merely to reassure the subject that there is no hocus-pocus, no supernatural or alternative reality, and that the cognitive associations that ring true are true in the present mind of the subject. The poet is on hand to reassure, to validate the responses of the subject to radical new perspectives into their own most intimate selves, and to relieve and dispel any accompanying trauma as grounded in the normalcy of human experience.202 203

CONCERNS AND LIMITATIONS OF POETRY THERAPY

In spite of its widespread appeal and broad range of applications, some concerns have been raised about the use of poetry therapy.

Some critics have pointed out it is possible for people to analyze a poem on a purely intellectual level, without any emotional involvement. This type of intellectualization may be more likely when complex poems are used, as a person might spend so much time trying to decipher the meaning of the poem that they lose sight of their emotions and spontaneous reactions. Poems that are unoriginal or filled with clichés are unlikely to stimulate individuals on a deep emotional level, or challenge them to think in ways promoting growth.

Just always keep in mind that poetry therapy may have little or no value for those individuals who simply do not enjoy poetry.

References:

Chavis, G.G. (2011). Poetry and story therapy: The healing power of creative expression. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Gooding, L. F. (2008). Finding your inner voice through song: Reaching adolescents with techniques common to poetry therapy and music therapy. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 21(4), 219-229.

International Federation for Biblio/Poetry Therapy. (n.d.). Summary of training requirements. Retrieved from http://ifbpt.org/obtaining-a-credential/getting-trained

Mazza, N. (2003). Poetry therapy: Theory and practice. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Olsen-McBride, L. (2009). Examining the influence of popular music and poetry therapy on the development of therapeutic factors in groups with at-risk adolescents (Doctoral dissertation).

Rossiter, C. (2004). Blessed and delighted: An interview with Arleen Hynes, poetry therapy pioneer. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 17(4), 215-222.

https://www.facebook.com/realpoetrytherapy

realpoetrytherapy@gmail.com

Poetry Therapy

Everyone wants to be free.

ven from the things that once gave us comfort.

We are like children who swap our blankets

For softer ground.

So why do you wait to be free

When the keys to your cage

Are hanging right outside your front door?

Reach through the bars with your hand

Stretch your fingers far and bend your will around the bars.

Your mind is your best friend, your best teacher, your best doctor,

Whether you believe it or not.

In spite of everything you’ve done to yourself,

Your mind really does care about you and often thinks of you, quite fondly.

Just let your mind mend itself

Heal yourself with a few choice words.

Your own words.

When you say:

The truth is not a cold tombstone

The truth is not a judgement

The truth is a flowering realisation inside your own living mind.

Pulling you outwards, & forwards, enraptured by Time.

When my breath and

My will are as one,

The universe swallows me

Whole.

A Short History of Poetry Therapy: Practice and Perfection by Igor Goldkind

On FaceBook, a discussion where questions are posed and answered: https://www.facebook.com/realpoetrytherapy/

The healing effect of words has long been recognized. As far back as 4000 BCE, early Egyptians wrote words on papyrus, dissolve them in liquid, and gave them to those who were ill as a form of medicine. In more recent history, reading and expressive writing have been employed as supplementary treatments for those experiencing mental or emotional distress. Pennsylvania Hospital, the first hospital established in the United States, employed this approach as early as the mid-1700s.

In the early 1800s, Dr. Benjamin Rush introduced poetry as a form of therapy to those being treated. In 1928, poet and pharmacist Eli Griefer began offering poems to people filling prescriptions and eventually started “poem-therapy” groups at two different hospitals with the support of psychiatrists Dr. Jack L. Leedy and Dr. Sam Spector. After Griefer’s death, Leedy and others continued to incorporate poetry into the therapeutic group process, eventually coming together to form the Association for Poetry Therapy (APT) in 1969.

Librarians also played a major role in the development of this approach to therapy. Arleen Hynes, one pioneer in this area, was a hospital librarian who began reading stories and poems aloud, facilitating discussions on the material and its relevance to each individual in order to better reach out to those being treated and encourage healing. In 1980, all leaders in the field were invited to a meeting to formalize guidelines for training and certification. At that meeting,  the National Association for Poetry Therapy (NAPT) was established.

the National Association for Poetry Therapy (NAPT) was established.

As interest grew, several books and articles were written to guide practitioners in the practice of poetry therapy. Hynes and Mary Hynes-Berry co-authored the 1986 publication Bibliotherapy – The Interactive Process: A Handbook. More recently, Nicholas Mazza outlined a model for effective poetry therapy, also discussing its clinical application, in Poetry Therapy: Theory and Practice.

The Journal of Poetry Therapy, established in 1987 by the NAPT, remains the most comprehensive source of information on current theory, practice, and research.

There is also a relationship between psychological healing and incantations; either repeated as a musical chant by the patient or in fact recited by the attending medicine man. Modern medicine and science of course scoff at the notion of magical incantations having healing or restorative powers as so much superstition. But this, of course, begs the question that if recitations and incantations had no evidential resort and no beneficial property then why would every single human culture have adopted the method and repeated it for several thousand years? Surely if there was nothing to vibrating air with the sound of one’s breath as well as the added stimulation of associative meaning being read cognitively by the patient’s mind; we would have given it and its sisters, singing and chanting aeons ago.

I am  not advocating a supernatural or spiritual causation for the effectiveness of poetry as a healing agent but rather the supra-natural mystical cause which is grounded first in human nature and behavior for which can be a myriad of imprecise explanations; none of which explain why it works.

not advocating a supernatural or spiritual causation for the effectiveness of poetry as a healing agent but rather the supra-natural mystical cause which is grounded first in human nature and behavior for which can be a myriad of imprecise explanations; none of which explain why it works.

Today, poetry therapy is practised internationally by hundreds of professionals, including poets, psychologists, psychiatrists, counsellors, social workers, educators and librarians. The approach has been used successfully in a number of settings—schools, community centers, libraries, hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and correctional institutions, to name a few.

How Does Poetry Therapy Work?

As part of therapy, some people may wish to explore feelings and memories buried in the subconscious and identify how they may relate to current life circumstances. Poetry is beneficial to this process as it can often be used as a vehicle for the expression of emotions that might otherwise be difficult to express

•Promote self-reflection and exploration, increasing self-awareness and helping individuals make sense of their world

•Help individuals redefine their situation by opening up new ways of perceiving reality

•Help therapists gain deeper insight into those they are treating

• In general, poetry therapists are free to choose from any poems they believe offer therapeutic value, but most tend to follow general guidelines.

It is recommended selected poems be concise, address universal emotions or experiences, offer some degree of hope, and contain plain language. Some poems commonly used in therapy are: “The Journey” by Mary Oliver “Talking to Grief” by Denise Levertov “The Armful” by Robert Frost “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” by William Wordsworth “Leaves of Grass” by Walt Whitman “Turtle Island” by Gary Snyder The poetry of Alan Watt, Allen Ginsberg and others.

Although the selection of material is often by the therapist, those being treated might be asked to bring to therapy a poem or other form of literature they identify with, as this may also provide valuable insight into their feelings and emotions.

My Technique in Poetry Therapy

A few different models of poetry therapy exist, but the one I’ve had the most success with is a Four Phased Progression of Attention:

Recognition – Focus – Intention – Action

In the receptive/recognition phase, the poet therapist merely guides the subject to focus on their issue. The aim is to establish concentration and cognitive focus on the details of the issue which are not revealed to the poet/therapist. Only until the poet/therapist feels confident that the subject is cognitively attuned to and non verbally focussed on the problem or issue of concern that they begin to ask suggestive questions as to how the subject feels, not thinks about their subject.

This provocation of emotion usually comes in three distinct phases of emotional content:

I. First is the one of the predicament, then the subject first becomes aware of the existence of the issue. This is the gateway phase where anticipatory feelings are registered and ideally conveyed through the prompting of the poet/therapist.

II. Then there is the full throttle stage when anticipation of the issue has given way to full experience of all emotions related to the issue. This is usually overwhelming (or it wouldn’t be “an issue” in the first place), and it is tantamount that the poet/guide leads the subject through distinct words to describe the layers of emotions experienced by the subject. Language and the use of the words is the key here because emotions always come in clusters of complexity that make it difficult for both poet/therapist and subject to distinguish and focus on underlying and suppress emotions.

“What kind of anger do you feel?”

“How would you describe your sadness”

“How much shame do you feel?

“What would you compare it to?”

Are typical of the questions a poet therapist would ask the subject.

This is a sophisticated method of word association but rather than creating bridges between seemingly disparate words, the goal is to drill down to the core emotions about the issue by uncovering and refining the language the subject has chosen.

Achieving exactitude of description is the task at hand. The Poet/Therapist makes careful notation of everything the subject says towards describing their emotion. It is important to keep them focused and not to succumb to intellectual distraction. Thoughts are illusions, emotions are facts.

Getting the subject to correctly and precisely describe the emotional facts of the matter at hand is the objective

III. The final phase is the exit strategy.

How do the feelings commence to recede? How does the issue recede back into the background? What are the parting emotions? Is there anxiety about the leaving? The anticipation of an issue yet unresolved? Or is the issue impermeable and subject to a rhythmic return?

Again, the subject’s wording, their adjectives, adverbs and phrases are the material of the poem.

At this point, there is usually a short break to give time for the subject to recover from the emotional transitions and for the Poet/Therapist to briefly skim their notes and begin to focus on the flow of adjectives. It is preferable if possible, to compose what amounts to a first draft, a flow of words which the poet can read back to the subject to confirm the accuracy of the flow.

At this first reading stage, it is possible to start interjecting logical bridges between the emotional descriptors. This is the creative factor unleashed. The Poet must be led by the subject to link coherent sequences between the emotional states. The poet suggests and the subject confirms or vetoes the phraseology, one line at a time.

Now we arrive at a second draft which is the property of the subject. It is their poem for which it is crucial that the subject now read the poem aloud and take ownership of its content. The subject can redraft the poem a third time in making it their own. But the physicality of uttering the words they have chosen to express their emotional state is an act of ownership and closure.

The Poet/Therapist can either email the finished poem to the subject, hand them his/her notes or rewrite the poem into a legible form. In any case, it is important that the Poet/Therapist ascribes the authorship of the poem to the client. If the client is hesitant to put their name to the poem than something is lacking in the poem and must be redressed or indeed started over again.

The key to the entire exercise is freedom of expression, honesty and then refinement; exacting the poem.

Other Approaches and Other Models

The process of writing can be both cathartic and empowering, often freeing blocked emotions or buried memories and giving voice to one’s concerns and strengths. Some people may doubt their ability to write creatively, but therapists can offer to support by explaining they do not have to use rhyme or a particular structure. Therapists might also provide stem poems from which to work or introduce sense poems for those who struggle with imagery. A Poet/Therapist might also share a poem with the individual and then ask them to select a line that touched them in some way and then use that line to start their own poem.

In group therapy, poems may be written individually or collaboratively. Group members are sometimes given a single word, topic, or sentence stem and asked to respond to it spontaneously. The contributions of group members are compiled to create a single poem which can then be used to stimulate group discussion. In couples therapy, the couple may be asked to write a dyadic poem by contributing alternating lines.

The symbolic/ceremonial component involves the use of metaphors, storytelling, and rituals as tools for effecting change. Metaphors, which are essentially symbols, can help individuals to explain complex emotions and experiences in a concise yet profound manner. Rituals may be particularly effective to help those who have experienced a loss or ending, such as a divorce or death of a loved one, to address their feelings around that event. Writing and then burning a letter to someone who died suddenly, for example, may be a helpful step in the process of accepting and coping with grief.

How Can Poetry Therapy Help You?

Poetry therapy has been used as part of the treatment approach for a number of concerns, including borderline personality, suicidal ideation, identity issues, perfectionism, and grief.

Research shows the method is frequently a beneficial part of the treatment process. Several studies also support poetry therapy as one approach to the treatment of depression, as it has been repeatedly shown to relieve depressive symptoms, improve self-esteem and self-understanding, and encourage the articulation of feelings. Researchers have also demonstrated poetry therapy’s ability to reduce anxiety and stress in people.

Those experiencing post-traumatic stress have also reported improved mental and emotional well-being as a result of poetry therapy. Some individuals who have survived trauma or abuse may have difficulty processing the experience cognitively and, as a result, suppress associated memories and emotions.

Through poetry therapy, many are able to integrate these feelings, reframe traumatic events, and develop a more positive outlook for the future. People experiencing addiction may find poetry therapy can help them explore their feelings regarding the substance abuse, perceive drug use in a new light, and develop or strengthen coping skills.

Poetry writing may also be a way for those with substance abuse issues to express their thoughts on treatment and behavior change. Some studies have shown poetry therapy can be of benefit to people with schizophrenia despite the linguistic and emotional deficits associated with the condition.

Poetry writing may be a helpful method of describing mental experiences and can allow therapists to better understand the thought processes of those they are treating. Poetry therapy has also helped some individuals with schizophrenia to improve social functioning skills and foster more organized thought processes. It is important to note in many instances, especially in cases of moderate to severe mental health concerns, poetry therapy is used in combination with another type of therapy, not as the sole approach to treatment.

Training for Poetry Therapists Poetry therapists receive literary as well as clinical training to enable them to be able to select literature appropriate for the healing process. While there is no university program in poetry therapy, the International Federation for Biblio-Poetry Therapy (IFBPT), the independent credentialing body for the profession, has developed specific training requirements. Several studies support poetry therapy as one approach to the treatment of depression, as it has been repeatedly shown to relieve depressive symptoms, improve self-esteem and self-understanding, and encourage the expression of feelings.

Concerns and Limitations of Poetry Therapy

In spite of its widespread appeal and broad range of application, some concerns have been raised about the use of poetry therapy. Some critics have pointed out it is possible for people to analyze a poem on a purely intellectual level, without any emotional involvement. This type of intellectualization may be more likely when complex poems are used, as a person might spend so much time trying to decipher the meaning of the poem that they lose sight of their emotions and spontaneous reactions. Poems that are unoriginal or filled with clichés are unlikely to stimulate individuals on a deep emotional level or challenge them to think in ways that promote growth. Just always keep in mind that poetry therapy may have little or no value for those individuals who simply do not enjoy poetry.

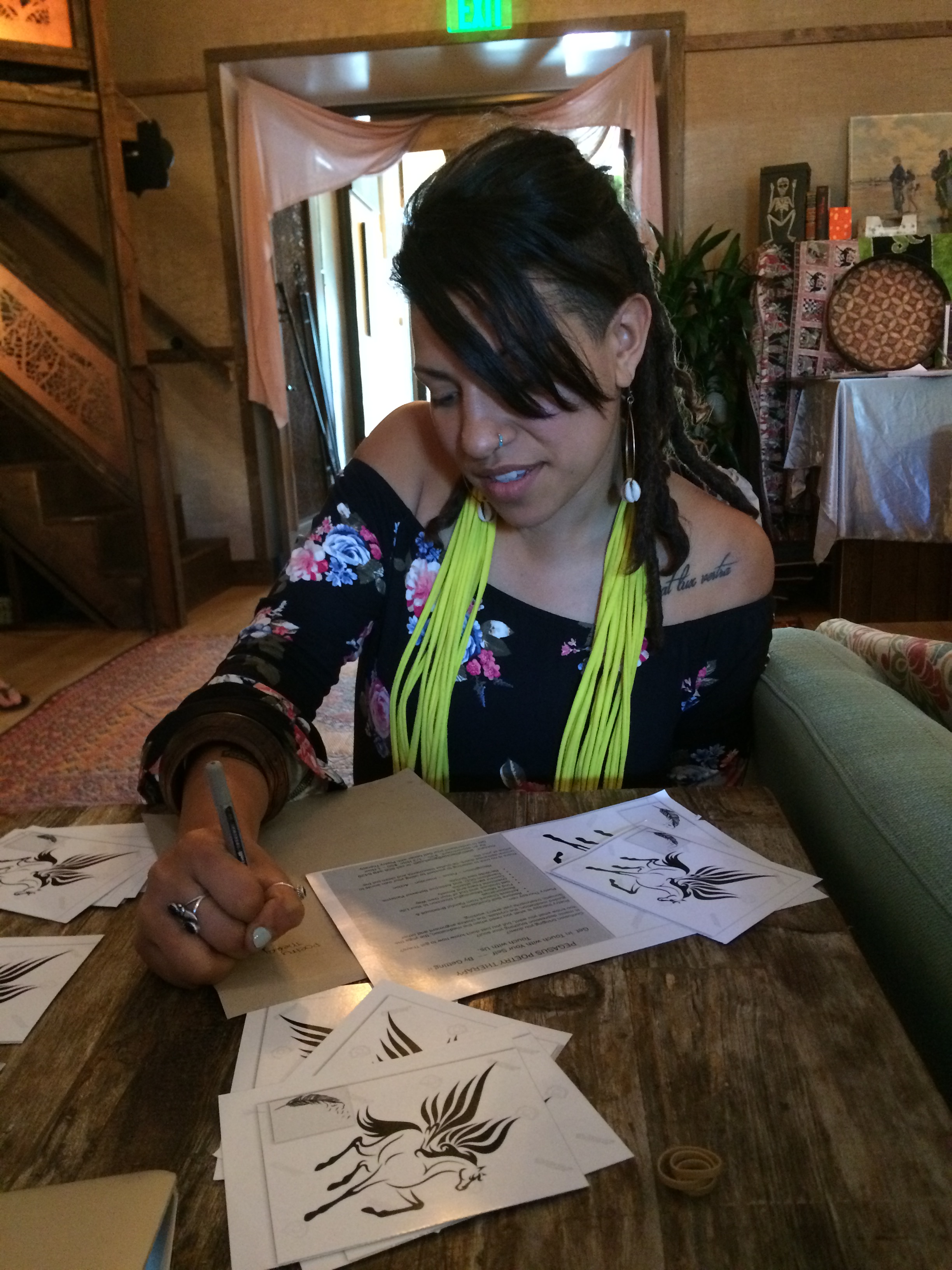

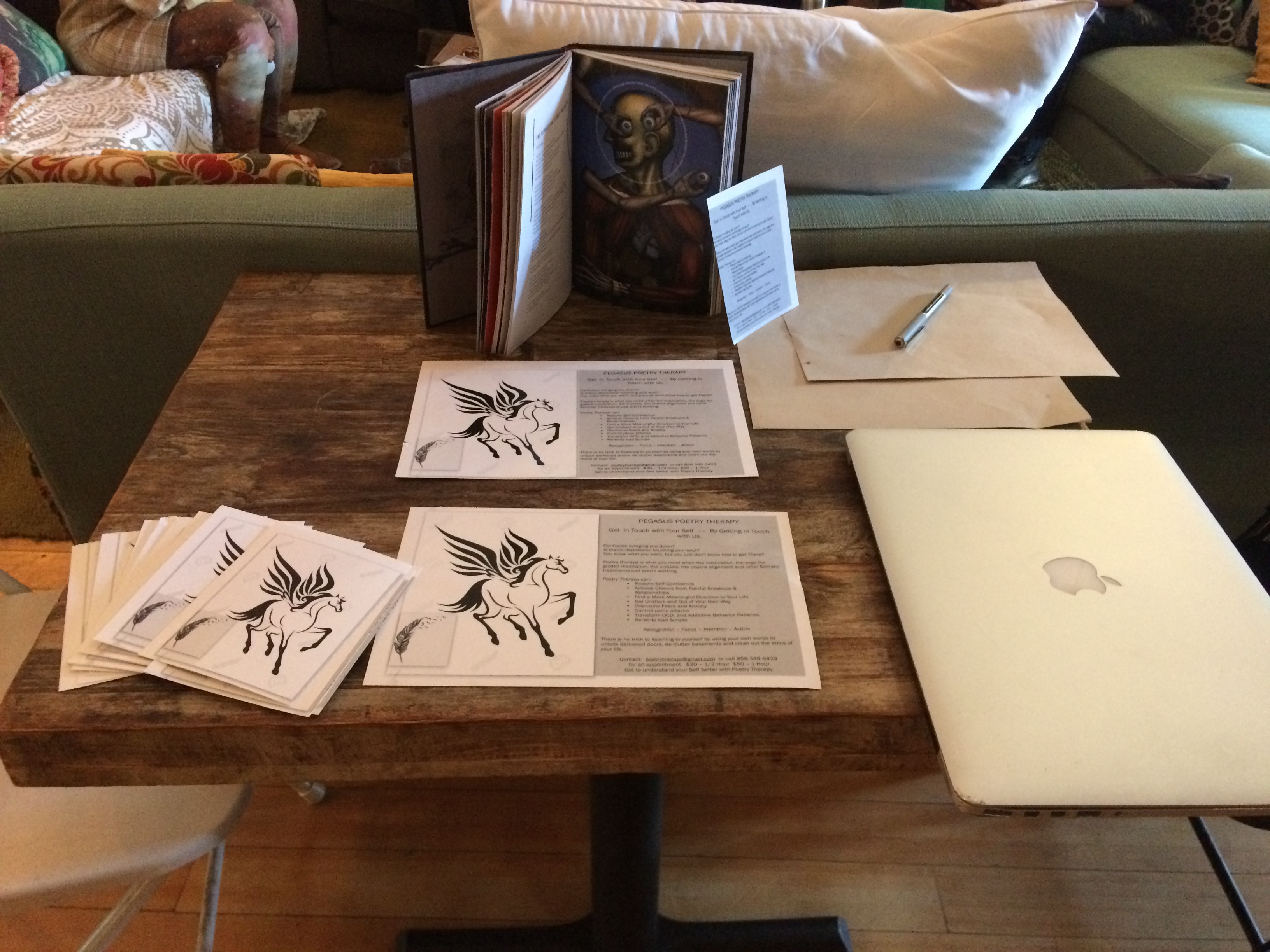

The Advertising Pitch:

Words are the Most Powerful Magic There Is

Sometimes Your Mind Has a Will of Its Own

With PEGASUS POETRY THERAPY you can

Learn How to Read Your Own Mind!

Confusion bringing you down?

Is manic depression touching your soul?

You know what you want, but you just don’t know how to get There?

Poetry therapy is what you need when the medication, the yoga, the guided meditation, the crystals, the chakra alignment and other Somatic treatments just aren’t working.

Some things only work when you let them work:

• Restore Self-Confidence

• Achieve Closure from Painful Relationship Breakups & Lost Loved Ones

• Find a More Meaningful Direction to Your Life

• Get Unstuck and Out of Your Own Way

• Overcome Fears and Anxiety

• Control panic attacks

• Change Addictive Behavior Patterns, like OCD

• Re-Write bad Scripts

Recognition > Focus > Intention > Action

There is no trick to listening to yourself and learning how choosing and rearranging your words can unlock darkened doors, de-clutter basements and clean out the attics of your life. Sometimes in merely one session.

There is no trick to listening to yourself and learning how choosing and rearranging your words can unlock darkened doors, de-clutter basements and clean out the attics of your life. Sometimes in merely one session.

Every Tuesday from 11:00 am until 6:30 pm at the

Inner Temple Inner Healing Center

at Eve’s Vegan Cafe 575 S. Coast Highway 101 Encinitas, CA

Contact: realpoetrytherapy@gmail.com or

Call 858 349 6429 for an appointment.

$50- 1/2 Hour $80 – 1 Hour

EXAMPLES & ENDORSEMENTS

PEGASUS POETRY THERAPY has only recently launched its online version via FaceTime, Skype or Facebook video.  Just add <poetry therapy> to your Skype contacts and schedule a date. Payments accepted through PayPal or Facebook cash. Here are some examples of the poetry achieved through PEGASUS POETRY THERAPY:

Just add <poetry therapy> to your Skype contacts and schedule a date. Payments accepted through PayPal or Facebook cash. Here are some examples of the poetry achieved through PEGASUS POETRY THERAPY:

I.

Narcissus in a Nutshell

I’ve lost the person locked within the situation

Like a nut dwells within its hard shell of fearful anger.

Escaping vulnerability

Hiding from the unknown.

Hard shells, hard feelings, hardness itself

The excitement of living days in the present

Belonging to the past

I will not let go of what I can recall but not relive

My belonging to that which encompasses myself

Another nut within its shell.

To belong is to exist

Without belonging there is Nothing and

I fear nothing most of all because I do not know it

And I fear what I do not know more than

I would remedy the pain of this loss with trustworthy tools

When two liquids are bonded as one

A single drop of poison poisons the whole glass

And betrayal is always poison no matter how little or how much

The glass of Narcissus’s tears is now empty

He has blinded himself rather than drink his own poison.

Instead he has left me to sip the bitter poison

Of fading better days.

Like a cat

Poised in stillness

Distracted by nothing

Ready to pounce

I will not surrender the pain.

I will not surrender the pain.

Because the pain is my memory of the happiness

We’ve now lost

A sweet nut within a bitter shell.

II.

The Martyr

Last night I saw you beatify a martyr

With a magical brush of gold belief.

You were serious and determined

But your brush strokes were light caresses

On a sky blue span of canvass

As you gently coaxed another image into being.

You remind me of my mother earth

Stern in her compassion

Willing to tolerate just so much from me

Before reining in my love

With her brushes.

And where you have drawn your line

‘Be careful’, you said to me on parting

But all the care in the world could not stop

My bulb from bursting

Rendering me blind in the speeding night

But still seeing with the golden light

Of the martyr you have shown me.

III.

Snake Heart

This sadness, this hopelessness

Will not be swatted away

Nor drowned by the busy work

Of the day to day.

It persists

Even when I am submerged in my bathtub.

The warm water rising from the bottom of my lungs.

Until I lose the will to breath

And the sadness becomes anger

Rising to the very top of my horns

Of my red-hot raging exhaustion.

How good to be angry!

I used to be afraid of snakes but no longer. I am hissing from the centre of my snake-heart

As you try and step over me.

Your eyes fail to see as you tread on my tail.

On my snake heart.

On my resolution without confrontation.

Without the owning of emotion

All that’s left for us is the hissing sound of machinery.

Coming Soon!

Share & Disseminate This With Your Friends

January 9, 2021 | Categories: art, book launch, books, comments about poetry, digital insurgency, Existentialism, Faith, Healing, literature, Meaning of Existence, Meditations, mental health, Mindfulness, new poetry, Paper Bag, physics, poetry, Poetry as therapy, Poetry Therapy, politics, Self-Therapy, spoken word, story-telling, Suicide, Therapy, Zen | Tags: Democracy, Donald Trump, philosophy, poetry, Poetry Therapy, Therapy | Leave a comment