On Poverty and Consciousness

A new acquaintance asked me why I endured relative poverty and uncertainty in California when I could easily take a tech copywriting or PR job and be living comfortably.

A new acquaintance asked me why I endured relative poverty and uncertainty in California when I could easily take a tech copywriting or PR job and be living comfortably.

I answered, for which I’m sure someone reading this might wonder the same.

The answer is not simple and all has to do with my commitment to art and to the art of writing. It’s somewhat like a religious or spiritual calling; certainly as requisite of sacrifice and discipline as a monastery. (Read James Joyce’s Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, if you need further elucidation on the subject). To become a great artist, which is what I believe I am becoming at this late stage of my life (or will at least die trying to be), takes total focus and constant dedication.

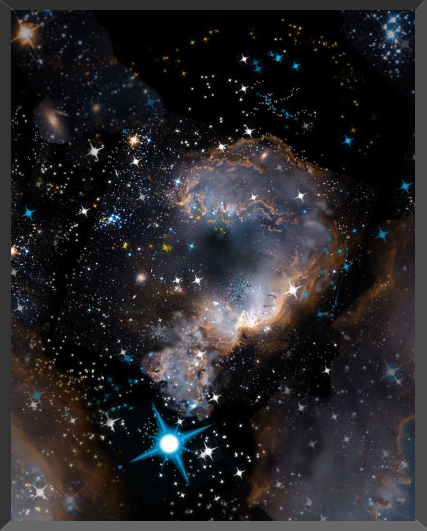

Not just to creation but to observation. Many of my best friends are not just poets and artists but scientists and mathematicians because they are processing their own observations through their own disciplines. When we talk and share words they read me and hear me, they comprehend how we’re all pursuing the same thing: the truth about life and the lives we are living.

Science and Art are really just two different vantage points in the same universe. During our Rennaisance there was no such separation between science, engineering and art. Just look at Da Vincis’s sketches if you don’t believe me. And this underlines the true failing of the formal education systems. No purely structured system can account for, much less process the unstructured data of experience.

But one truth I have learnt along this way is that we are all connected; both as a species and as sentient beings. Not just to those existing in the moment we all share but for all of us, from the very beginnings of awareness and rational self-consciousness. We are all brothers and sisters of the same mind, the same awareness that is awake and cognicent.

We all share the same biology of the mind.

I imagine that when extraterrestrial sentient life is contacted, it will be the poets and artists most open to the new who will not only best describe and communicate qualitative meanings with them but decipher their language(s) to communicate with them (more of “us”?), before the actual scientists can interpret their data and the military can rationalize the threat.

From the point of commonality; this sentience itself has a common shape or form in all of us throughout time and geography. It is our human nature.

My words try to sketch its outline.

Without needing to name a god, the Buddhists have been attempting to describe this commonality of all sentient beings, for thousands of years. In art and yes, in poetry too.

It’s what poetry is for: to describe the indescribable that is true for all of us, to all of us.

The known shining its single torch down a darkened corridor to the unknown.

The unknown (not the unknowable), has always been our mind’s final frontier.

We weren’t born yesterday. We did not just become aware of consciousness. The history of consciousness is the history of us, of the ‘you’ that is reading and comprehending these words.

You are no different in awareness than the Neanderthal who stumbled out of her cave and looked up at the stars in wonder. Every astronomer I have ever known harbors that exact same wonder. Our tools maybe bigger, faster and deadlier but our minds haven’t changed, just adapted to our tools. They’re physiologically still the same; and only enhanced by the evolution of language, both associative, symbolic and metaphoric.

This is where we alll connect. The commonality of our senses’ perception and their comprehension. This is what is meant by ‘realisation’. When we make the world real. When we realise that the truths we know from our senses connect us to the world as intimately as to each other.

These are the materials I use to create art.

But why not get a day job?

I will have to.

I have learned all I can stomach for now about the tangible reality of poverty. I have made some great and tragic friends outside my walls of privilege and comfort. But when I first detected my dwindling resources, I panicked. I borrowed gas money from friends, slept in beachside campsites for free and spent too many days in chic cafes nursing one cup of coffee and a refill just to write, just to connect with the non poverished. I. applied for every job I was qualified for and hustled my books even harder.

But this did not avert my panic and the fear, until it passed of its own. And you already knnow: nothing is ever as bad or as long as we first imagine it to be. That’s when I understood how many of my needs, weren’t needs at all and that I could live without the comforting requisites of a middle class existence, just fine. In some ways better.

Less consumption = less waste.There’s what I want and what I can have and if I diminish my wants, I can have have everything I want.

When you don’t have any money, you don’t spend any money and that initself is a good thing.

The last argument that pursuaded me of the virtue of experiencing this lifestyle is that if I really wanted to write for wider audience in a profound and meaningful way, that I might need to understand and empathize with the truth of our human condition across the entire economic spectrum, not just those who can afford to buy books

And the truth is that the vast majority of “us”do not live a middle class lifestyle and that the majority of “us” struggle every day to earn what is called a living and yet seldom ressembles it.

I have met so many, so many poor people living on the streets in one of the wealthiest cities in the wealthiest state in the union, in the wealthiest nation in the world.

None of us can afford to rest within our illusion of justice and freedom until poverty is no longer the default state of the human condition in America. Remember, poverty is a prison from which escape is difficult. But if we truly want to say that we live in the land of the free, then we must free our citizens from the prison of poverty.They are “us” as well. Not charitable”us”, not pitiful “us”, not lazy, drug taking, alcoholic “us”.

Just us.

I have talked in depth with enough of the so-called “homeless”. to recognize them for who they really are: The Poor. You know, those people Jesus was always talking about and Charles Dickens and Emile Zola wrote about? The idea that those without homes choose to live that way is a bigoted urban myth that need to be quashed.

Yes, may of the poor have real problems with alcohol, drugs and severe mental illness. But so does every other group and class of people I have ever known. The rich and the middle class aren’t exempt from alcohol, drugs and craziness; in fact they can afford more!

How then are we less connected as human beings?

Or is “humaness” only measured by level of income?

When I moved back to California to look after my mother, I was immediately struck by the avalanche of poverty that had engulfed my home town. As is every other foreign visitor to California, by the way. No tour of Balboa Park or visit to Sea World can eradicate the open poverty that everyone can see on the streets of San Diego. Which now more closely ressemble the streets of Port-au-Prince, Haiti or the extreme poverty that can be found in some places in Mexico, than any American city.

The first thing that went was the last vestage of regional or even national pride.

It is a crime against humanity for so rich a city as San Diego to maintain the level of homeless poverty that is evident to anyone who visits us. It is “our” fault. Because we are also connected to the impoverished and the socially weak.

You know, what Jesus was saying.

If I am to write the truth for those who want to read or hear the truth, then I ought to know what is lying outside the walls my middle class habits and worldview. What is it really like, not just for the impoverished but for the vast majority of Californians who also now live beyond the walls of middle class sensibilities, paycheck by paycheck?

Haunted by the memories of its long gone comforts.

What does it mean to be a human being living in America right now, in 2020. Aren’t we all supposed to have jertpacks by now?

What is the Truth of our American selves?

As Tony Morriosn said “The whole point of freedom is to free others”.

To my friends who have offered their support, I thank each one of you.

I will never forget your kindness and your humaness.

Yes I have a new book coming out in the fast approaching Spring.

It’s entitled TAKE A DEEP BREATH, A Book of Remedies and will feature much of the writing and accounts of experiences of truth that I have had living in California these last 5 years.

I hope that you will take a look.

The Stars

There are few shreds of dignity left

When you drown face down in your own back street gutter.

You can cry out as loud as an archangel’s horn, if you like.

It won’t do you any good, or any harm either.

You still can’t silence the wind or turn back the tide.

Fate is nothing personal.

It’s just the universe catching up and then passing you by.

Your dream of yourself evaporates,

Forming clouds that obscure the night’s sky.

The stars are leaving you now, blinking out one by one.

This is the last moment of your own

self-awareness.

Your last chance to figure out what the fuck’s been going on.

It’s very much like the moment you first awoke

Although your mother’s smile is nowhere to be found

All that remains of her unlimited love is your fast fading memory

The sound of her voice calling out to you to come home now,

In the far distance,

From where the stars have gone to mourn your passing.

Confetti

There’s an emptiness at the heart of any space:

The air that escapes a room; an unanswered echo, a vacant womb.

There’s an emptiness in my heart

That reminds me

All of my ideas are empty.

Floating leaves from a fumbled folder.

Coloured streams falling from the sky.

This emptiness reminds me

How slight my desires really are

How gently they fall from the sky

A confetti of mercy and discarded emotions,

They are in the end,

Compared to nothing,

Merely the litter from an emptied mind.

One Without the Other

Life and death are dark and light.

Like black and white,

You need one to see the other.

For without the other,

You will never see the one.

5 Submissions of My Latest Work

Life is Always Replaceable

Being is Becoming Still

Existence is a limitless screen of emptiness,

Insomniac Awareness

The Last Halo of Hope.

Pebbles

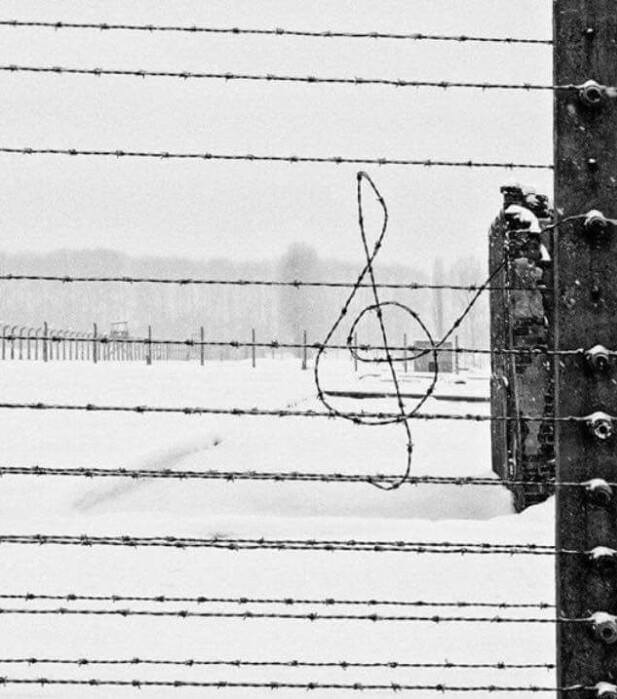

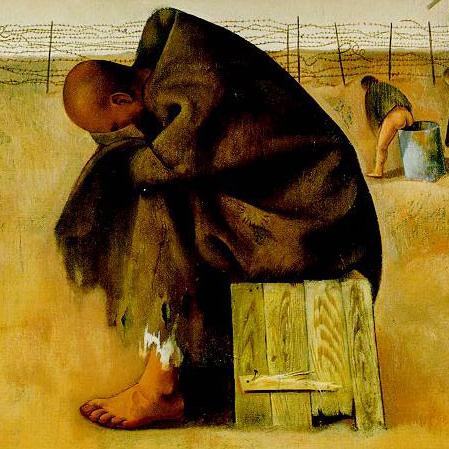

The Holocaust Survives

No other single event in history had more of an impact on the 20th century and by consequence the present 21st, than the mass brutalisation of families or men, women and children in the camps and now in the Syrian refugee camps in Lebanon.

No other single event in history had more of an impact on the 20th century and by consequence the present 21st, than the mass brutalisation of families or men, women and children in the camps and now in the Syrian refugee camps in Lebanon.

L’Chaim

Master of Puzzles

By Igor Goldkind

Ivan Moscovich has created more brain-teasers than most people have solved crosswords. Igor Goldkind set out to piece together his fascinating and harrowing life.

Ivan Moscovich has his life’s work wrapped up in a bundle of about 10,000 pages of A4 paper. On those pages there are some 5,000 separate puzzles, puzzles that range from the hang-on-let’s-look-OK-I-see to beyond the fiendish. Some are variations on themes, some utter one-offs. Some are to be made on paper or card, some are designs for tricky little – or big – devices. Moscovich calls them the S.A.M. archive – science, art and mathematics. The puzzles use the techniques of bafflement to teach, and they use beauty to bemuse.

Moscovich has been making puzzles since the 1960s. Now, at the age of 70, he’s looking to transform that life’s work into new formats. He and his colleagues have started up a new company to take the ideas on those 10,000 pages and put them to work in the digital arena. Moscovich is sure that there is room for them. Having looked with interest at hits like Seventh Guest, which friends told him were bringing new life to the world of puzzles, he was profoundly unimpressed. The puzzles were hard, sure (if you weren’t Moscovich, that is), but they were variations on a small number of underlying tricks, and they didn’t add up to more than just a set of puzzles. Moscovich thought that he – or people mining his archives in digital form – could do better.

“In digital media you can build overlapping linear trees, using the media to interrelate the concepts for the user. It’s important with any problem to see – at the same time – the different paths that can take you to a solution. Certainly this is the best way to explain scientific and mathematical concepts.” The collection of puzzles becomes a sort of puzzle itself: a maze, something to find one’s way through, something more than the sum of its parts.

Ivan is looking forward to trying to put all this into practice – not least because he enjoys the attitude of the people he’ll be working with. The way that games designers and programmers think fits into his world perfectly. He loves to be with people who are bored when they’re not trying something new, even impossible, when they’re not seeking a new solution. And he can make sense of himself by being part of a group; in fact, it has saved his life before now.

Ivan likes people who try to make sense of the pieces. That, in part, is how he got into puzzles – his delight in their ability to teach eager minds. As well as making puzzles for books and toys, he has used them as serious teaching tools for engineers – and pioneered the art of transforming the counterintuitive insights of puzzling into science museums with interactive displays. Putting together the pieces of an idea is much more important than putting together the pieces of a puzzle. The wonder is that by getting someone to do the latter, you can let them do the former.

A life in fragments

Moscovich’s own life is a bewildering array of puzzle fragments. Having met him on a CD-ROM project and learned some of his history, I started to wonder how to reassemble the fragments – and what they could be made into. One of the answers is a charming, brilliant septuagenarian. Another is 10,000 pages of A4. And a third might be a technological passage through the 20th century, from the industrialisation of death to the pursuit of pleasure. A journey that charts the territory of the 20th century’s technological revolutions and its human upheavals, from the Balkans to California, from museums to the Israeli defence industry, from the ruins of Austro-Hungary to the digital age, from railways to death camps.Moscovich’s parents were Hungarian, but he was born in Novi Sad, a small Serbian town. He still retains a central European accent that, to my ears (and probably to yours) sounds like the definitive voice of modern science and mathematics. “My father was a Hungarian who escaped from Hungary into Yugoslavia after the First World War. He was a painter by profession, but in order to make a living at that time he opened a photographic studio which became very successful. He named his studio Photo Ivan, after me.”

His description of an everyday childhood in Novi Sad paints a familiar

portrait of a middle-class craftsman’s family, complete with Yiddish grandmother and old-world family meals – and none of the hothouse intellectual atmosphere that produced Leo Szilard, John von Neumann, Kurt Gödel and other thinkers who left Budapest to dominate 19th-century thought. There was little to suggest Ivan’s strengths in science or mathematics – except, perhaps, a boyish infatuation with model aeroplane kits. He had, however, inherited from his father an inclination for drawing, and his father’s habit of tinkering with various gadgets – including an early air brush – to enhance his pictures was a constant delight to Ivan.

But when he reached technical high school, Ivan fell under the influence of a mathematics teacher given to explaining the precepts of science by means of science fiction. Ivan’s teacher opened up the world of mathematics by making problem solving fun. Ivan was entranced by the maths – and, later, showed that he had learned the method, too: rigorous scientific thinking through the lens of art and storytelling.

By then, though, the Hungarian fascists had invaded. They met with little resistance. And, soon afterwards, they took Ivan’s father from him. “Before they took him, he asked a Hungarian officer if he could say goodbye to my mother and in their final embrace he slipped this ring onto her finger.” Ivan holds up his hand and shows me an ornate gold band studded with eight small diamonds. It is the only surviving memento of Ivan’s youth; everything else was lost in the Holocaust. Ivan’s father joined 6,000 Jews and 4,000 Serbs executed en masse and thrown beneath the ice of the frozen Danube. All in one day.

Ivan continued his studies until the end of 1943, when the Hungarians “got cold feet” and the Germans invaded. “We really didn’t have any knowledge of what was happening in Poland in the ghettos or with the Nazis. We all hated the Hungarian fascists, but I still knew and liked Germans and, you know, communications were very different then; telephones didn’t work internationally. We were really disconnected from the rest of the world.”

When a Hungarian Jew escaped from Auschwitz and fled to Budapest to warn the Jewish community of the death camps, few believed him. So Ivan Moscovich was deported to Auschwitz at the age of 17.

“It meant stepping out of one world into another one. I was sent with my grandfather, my grandmother and my mother. When we arrived, my grandparents were immediately taken to the crematoria. My mother stayed in Auschwitz the whole time. After three or four weeks I was taken out of Auschwitz into one of the surrounding work camps. Young people were sent to work. I worked at laying rail lines.” The Nazi system was to provide rations for six months survival, after which the workers were supposed to starve to death in order to make room for new inmates. The meticulousness by which the operation was organised was not lost on Ivan. Nor would the memory escape him when two years later he found himself again working on train rails.

By that time he and, miraculously, his mother were back in Novi Sad. An acquaintance in the Ministry of Transport offered him a research position in the effort to repair Yugoslavia’s war-torn railway system. The post involved testing an enormous German machine that used high electrical wattage to weld rail lines together, a then untested invention. Mounted on a train carriage, Ivan travelled with the machine throughout Yugoslavia, in charge of the welding team. The machine was so successful that Ivan soon found himself elevated to a lofty position within Tito’s Ministry of Transport, accountable only to the deputy minister himself.

“There I was, a simple technician, at the age of 20, and I had all this power and no boss, really. People thought I was a top-shot communist because everybody had to do exactly what I wanted. The project became more and more successful, our production was way up and I was given orders to enlist more and more technicians for my team. One day I was called in by the deputy minister and was told that in order to create a 24-hour work shift, I was to take on 50 German prisoners of war.”

So, two years after surviving the German work camps, he was given control over a work team comprising high ranking German officers and regular soldiers, some Wehrmacht, some SS. He could have done anything he wanted. He could have shot them all and easily justified his actions to the authorities. He could have tortured them to death with gruelling work. He could have snapped his fingers and made them all disappear. But Ivan Moscovich had responsibilities, a quota to fill and a marvellous welding contraption to keep running.

“I had ten kilometres of rails to get out that week and it was a real dilemma whether to screw the Germans or to try to get the best output from them. I decided to increase their rations to get more work out of them, and sure enough they were grateful and worked even harder, which increased the output. I was very, very tough with them and I think they were scared of me. But I never revealed to them that I was a camp survivor. They worked for six months and then Tito released the prisoners.”

As it happens, Moscovich only worked on the German railways for six months. “I was lucky for the first six months. It was very important for survival in the camps to be with your people, your clan of friends and family;

it made life easier. You couldn’t get ill, because that meant execution, but curiously, if you could show a work-related injury, a visible wound, you could be seen by the SS and granted a day or two of hospital. One day I announced myself with a bad wound. While everyone else went on work detail I was left in the enormous courtyard with a broom to clean up, completely by myself. Suddenly the gate opened and a commandant’s car stormed into the courtyard and headed straight for me. The German officer jumped down from his car, grabbed me by the scruff of the neck, threw me onto the platform of the vehicle and drove off. I was kidnapped.” Later Ivan learned that there had been an escape from a neighbouring camp and the camp commandant had stolen Ivan to make up his tally of inmates. The mathematics of death had to add up.

“Up to this point all of my feelings had been one single feeling: an enormous outrage. Rage that somebody, anybody, another power, could take me away from my decisions, my everyday life, and put me in an environment where whatever happened was not under my control. I was young and maybe too strong an individualist, but it was rage that kept me alive.” In the new camp this life-sustaining anger was broken, until he discovered a distant

Hungarian cousin running the camp’s kitchens and being the “godfather” of the camp. Then he found some school friends of his father’s. For several weeks Ivan rebuilt his spirits and his body. Then the Russians pushed back the German line, and the SS made their lethal preparations for evacuating Auschwitz.

The problem to solve was – how to survive.

The Museum Man

In 1952 Ivan found a new clan – and became a leader. He set out for Israel to join his now remarried mother. On the boat to Haifa, Ivan was approached by Israeli officials interested in his skills and qualifications. The new state was hungry for skilled technicians. By the time Ivan reached Haifa he already had a position in the Ministry of Defence waiting for him. “In my group there were mainly these Yugoslav and Hungarian technicians without any training in science and mathematics. The language problem was enormous, and here was this group of technicians involved in scientific research without any basis in the field. I don’t know how it happened, but I was selected as someone who could teach the other members of the group some basic science.

My boss wanted me to instruct them outside of a formal classroom using demonstrations, models and visual means. That was really the start that put me in the direction of puzzle making.”Ivan found himself playing around with visualisations and experiments. He worked hard to come up with ways in which complex ideas could be explained visually, not so much to convey a deep academic knowledge of science and mathematics but to engender an intuitive grasp of the subjects and, most important of all, to instill the knack of problem solving needed to tackle more important scientific and technological puzzles.

By the end of the 1950s, Moscovich was creating puzzles almost all the time, and practice had revealed a rare gift for making puzzles that could be revisited, puzzles that retained a depth, an impact, even after they had been solved. “I tried to design models that were compact and effective, and in which the experiments could be repeated a number of times. This required completely original design conceptualisations. My boss, Ernst David Bergman, was the leading scientist in Israel at the time, and founder of the Weizmann Institute. He loved my work, and it was he who had the idea that some of those objects I had designed could be exhibited. That was the basis of the founding of a science museum.”

In 1959 Tel Aviv established its Museum of Science and Technology, the first of its kind in Israel. Ivan worked non-stop for two-and- a-half years converting five disused British barracks into a museum, begging and borrowing every available resource. The museum finally opened in 1964 with Ivan as its curator and director. It was the first science museum to emphasise hands-on, interactive exhibitions, and it quickly attracted international attention. His position as curator became a springboard from which to explore and express his interest in art, science and mathematics, and to do it all with the benefit of a growing international reputation.

In 1965 Frank Oppenheimer, brother of the more famous Robert, having heard of Ivan’s fantastic museum to science, visited Tel Aviv with Admiral Lewis Strauss, chairman of the US Atomic Energy Commission. The two became fast friends, sharing a childlike fascination for technology and science as well as knowledge of the darker side of machines and technology. This was four years before the opening of the Exploratorium in San Francisco, for which Oppenheimer imported many of Ivan’s installations. Some remain on exhibit to this day.

The puzzle of death

In 1944, while Oppenheimer was working with his brother on the problems of designing the first atomic bombs, Moscovich was on the death march to Bergen-Belsen. Here, too, the problem was how to survive. “Everybody said those who stayed, declaring themselves ill, would be shot. As it happens, they were liberated by the Russians two weeks later. And we walked barefoot and nearly naked through the worst winter of the century, westward to Bergen-Belsen.”At Bergen-Belsen, the last stop for the Final Solution, Ivan gave up all hope. He had been assigned to a work detail in the then still beautiful city of Hildesheim, near Hanover.

“Near where I worked was a statue of the mathematician Leibniz with beautiful writing on it.

And it was so strange that after so long in hell, I am seeing that statue. I felt I was being visited by a ghost, an image of the real world I had left behind. It was then, only then, that I remembered my previous life, my teachers, my studies of mathematics and all that. Up till then my memories had been blocked out. It’s impossible to imagine that every minute, every second of life in the camps, you were only thinking of survival; there was no room for any other thinking. But here was this beautiful statue of Leibniz that reminded me of the real world.”After two weeks working in Leibniz’s shadow, “I heard this strange noise … mmmmmmmmmmmm … that filled the air, and we suddenly realised that the sky was filled with planes. The next second everything was on fire. It was the Allied carpet bombing of Hildesheim. I saw German soldiers burning, running, and everything became chaos. I ran. After a while I stopped and looked back at the city, which was one big torch. I found myself alone in a giant field, a free man. But a free man in pyjamas, a free man with nowhere to go. I weighed 45 kilos.” Ivan turned around and started walking back to the depot. With his camp clothes, his inverted mohawk, there was nowhere to run. A German woman ran out of her house and thrust a chicken leg into his hand; she never said a word.

Recaptured, he was beaten and sent back to the camp. The dead lay in their thousands. “One barracks the Germans were using to fill with dead bodies, hundreds of dead bodies. After work one evening, I decided that instead of going back to our sleeping area that I would crawl to the top of this mountain of bodies and find myself a horizontal place. There was a slot at the top where I could see what was happening outside. I slept there for five, six days; I don’t have any notion about how much time passed. It was bliss to sleep; quiet and beautiful. It was no problem sleeping on a bed of a hundred dead bodies. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have lasted.

“One day I awoke from my sleep to complete silence. I looked through the slot to see the camp was completely deserted. Suddenly through the main entrance, which I had in my view, drove a single jeep with four English officers that stopped in the middle of the square. I rolled down the hill of bodies like a log and then I felt like I was running but I must have been moving very, very slowly. I was, I think, one of the very first to reach the jeep, and you know those guys were looking at us like they were seeing aliens for the very first time. Like first contact.” He collapsed into the arms of an English officer.

Moscovich was deathly ill. By the time that English officer caught up with him again, in a local hospital, he looked unlikely to survive. So the officer found a German doctor and frog-marched him to Ivan’s bedside. The Englishman pointed his revolver at the terrified doctor’s head and said, “If this patient dies here, you die here.”

Ivan Moscovich did not die – nor, at that point, did the German doctor. Ivan was transferred to a Red Cross hospital in a small town in Sweden – a town so boring, he now swears, that the local newspaper actually ran daily updates on Ivan’s weight gain for lack of more interesting scoops. Ivan describes his slow recovery as matter-of-factly as everything else.

“At a certain moment you know, the organism decided,

‘OK, we’re going to stay in this world. ”

Toy story

In the mid-1960s, as his fame grew in Israel and beyond, another new world opened for Ivan Moscovich. “I was working on a puzzle at my desk one day when one of the ushers came in and said a couple of tourists wanted to see me. I was busy and didn’t have the time. The usher came back and said they only want five minutes of your time and they wouldn’t give up. So I agreed to see them, Mr and Mrs Eliot Handler. I wasn’t very enthusiastic but we talked and then Mrs Handler said ‘I would like our chaps in California to see your puzzles; are you ready to come over to California?’

I didn’t take them very seriously. Two weeks later I received a call from a travel agent who had a ticket waiting for me to go to California to visit Mattel.”Eliot and Ruth Handler founded and owned Mattel Toys. Its twelve-storey building in Hawthorne was the centre of America’s toy industry. Sales of their Barbie dolls were colossal, but the Handlers were keen to expand the Mattel range beyond just dolls. When Ivan came out to visit them they immediately offered him a three-year open contract to create games and puzzles for US$25,000 (£16,000) a year. His “Brain Drain” puzzle game promptly sold a million copies worldwide. This success was repeated with a series of puzzles including “Play It Again Fun”, “Visual Brainstorms”, “The Brain Power Decathlon” and “The Hinge”. Soon toy and games manufacturers from Japan to Europe were clamouring for more and more puzzles from the master. Ivan Moscovich’s gift had found the most widespread of all its expressions.

Fitting together the pieces

Somehow, all these pieces add together to produce a remarkably creative man, and one with a unique vantage point. Ivan has seen countries destroyed, reconstructed and created afresh. He has faced the most utterly depersonalising totalitarianism ever attempted, and rejoiced in the individual quirkiness of children’s imaginations. At an age where most seek nothing new at all, he is embracing the digital world with the enthusiasm of a seven-year-old offered a Game Boy.

How does he see the end of the century?

“At present we are in a greater need for a fresh creative spirit than in any other period of human history. Less and less experience is being gained directly through activities. Sensations tend to reach us increasingly only after passing through layers of media filters. Children manipulate electronic gadgets and play with computers, which is all very well, but ultimately lacks perspicuity and full sensual enrichment.

I hope to create open-ended concepts that trigger chain reactions. Ideally, the player plays my game, solves the problems and is motivated to invent his or her own variations of rules, ultimately creating his or her own games, puzzles and aesthetic structures.”He has an avowed predilection for the physical. You can see it in his hands as he solves his puzzles. But Ivan sees unique possibilities in the digital world, possibilities that flow from the nature of his puzzles. “I’ve already published several books of my puzzles, but in a book you are restricted to the lin- ear progression of page after page, without much freedom. To interrelate the conceptual links between problems and solutions you need to be able to cross reference non-linearly, which is what a CD-ROM does.” After all, this is the point of his S.A.M. archive – that it combines science, art and mathematics as different paths to the same goal. The trajectories can be changed forever; the solutions will still provide the improvements of the self that Moscovich cares about.

“You know, humanity has been defined in various ways. For instance, as Homo habilis, skilful man; as Homo sapiens, wise man. I prefer Homo ludens, playful man, as the best definition of modern 20th-century human beings.” It was a hopeful definition that Johan Huizinga came up with in the late ’30s, at the time that young Ivan was learning science through science fiction – but the hope was serious and fearful. Huizinga was quite aware that playfulness had its dangerous side, and that the coming war would be a great, dark game; it was peace, he always said, that was the serious business.

These days, Ivan Moscovich is at peace. He lives a quiet life with his wife Anitta in west London. Within him, though, you can sense the machines within machines working, a vast inner factory of the abstract. It is hard to imagine him without them – even in the worst places the century’s history has to offer. I asked him whether his puzzling mind had helped him in Auschwitz, in Belsen; whether he had made his retreat into a private world of abstraction and pure thought.

“No. You know, it’s very difficult to explain, to understand. All of your time, all of your energy, all of your thinking is just focused on one thing: surviving.”

He did. And from the simple fact of survival he has pulled together the fragments of his life into a living inspiration for the rest of us – a puzzle worth thinking about.

Igor Goldkind writes science fiction, comics and essays, and lectures on technology and culture.

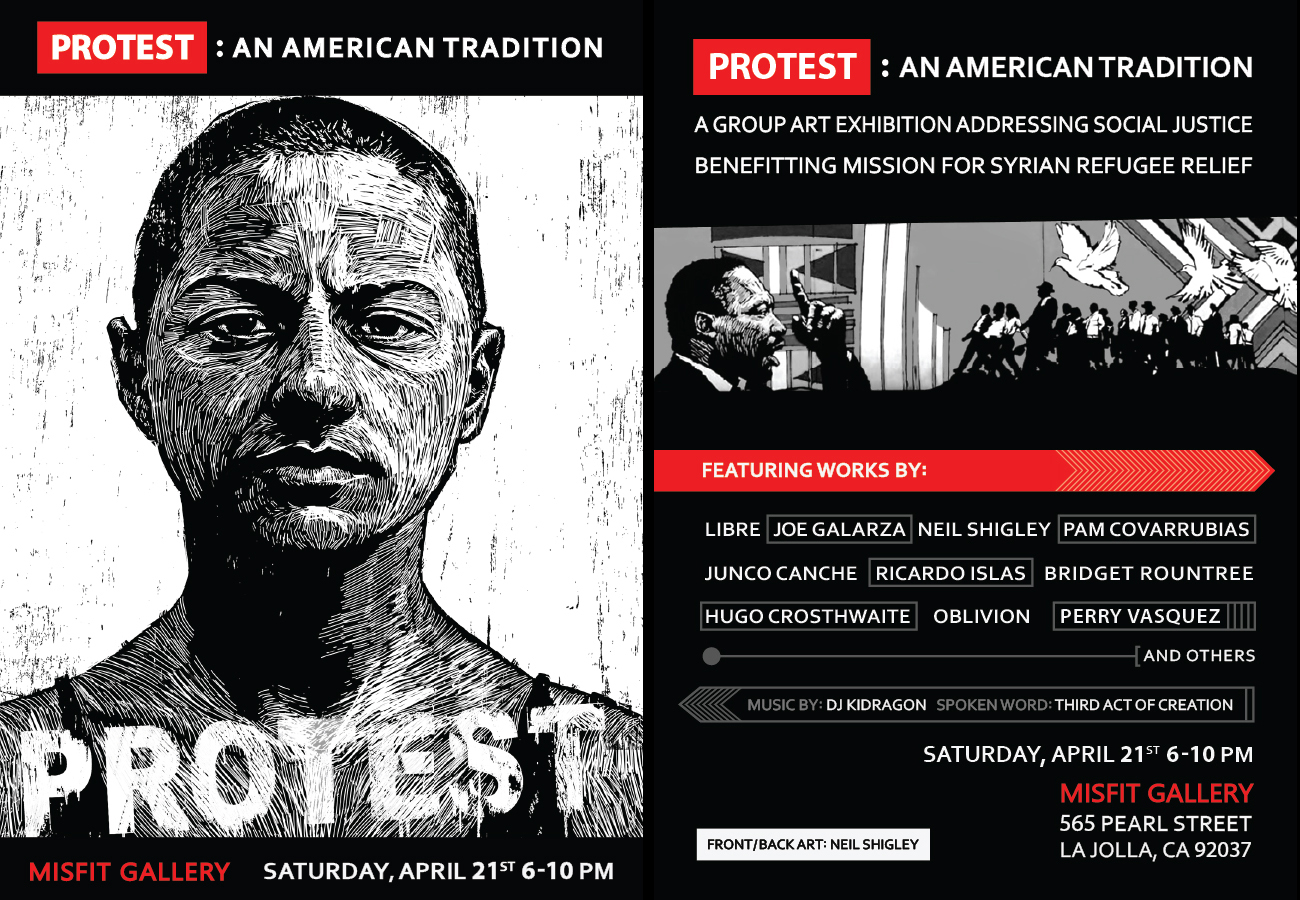

If you are concerned with the Syrian refugee crisis, the largest forced mass emigration of refugees since the Jews escaped Germany and Poland, there is something you can do. Inform your self through the Syrian American Medical Society who are running projects and providing medical supplies to the victims of the dictator Assad’s brutal and genocidal war against his own people.

Participate, if you live in southern California by attending a special exhibition of protest art at The Misfit Gallery in La Jolla California on April 21st.,

@ 565 Pearl Street. 92037 6-10 pm

I will be reading my published and unpublished work in the Spoken Word progamme as well as performing with The Third Act of Creation. But there’s much, much more. It’s a celebration of human rights and protest art to raise money for SAMS and also to join others in Mindful Resistance to the tyranny, bigotry and corruption in our present government and around the world. WE are THE PEOPLE, so instead of just complaining or getting depressed,

Let’s do something!

The Third Act of Creation

The Third Act of Creation

When I sit at my desk in the barely blinking dawn,

I sit at the helm of a Starship.

Each dimension of time or space is available to me

To go anywhere I want to.

With the flick of a switch and a weird background sound

The course can be faithfully plotted,

At just the right warp speed to be there, be heroic and be back before dinner.

As safe as the hum of my engines.

When I sit at my desk in the mid-morning blue light that pierces

My east facing windows.

I pray that I can write something today,

I pray that I still have something to say.

I pray that I still have something to say.

My eyes are drawn to the street just beneath me,

That winds around the standing tree,

Just outside my window.

There is a spoonful of sunshine in my coffee.

When I sit at my desk in the midday sun

At the zenith of all of Creation,

I know that the bright light that now floods my room,

Will wash the shadows of doubt from these walls.

I still hear that first sound,

The Bang! that expands the spaces around.

I can feel how the act of creation was never just one moment long gone ago.

But a circus of new sensations, an ongoing show.

Will too soon leave us behind sleeping eternity away.

When I sit at my desk in the mid-afternoon sun

And the light of creation slowly dwindles,

I can reflect on all the things that I’ve done

While counting the tasks that remain to lie in the sun.

When I sit at my desk at dusk’s twilight time

When light and darkness are twined,

Each wrestles the other to the ground.

I know that darkness will eventually swallow,

The fading strength of the light.

The time for my bed is just insight

And the twin brothers have given up their fight.

When I sit at my desk in the heart of the darkness

I know that death is hiding in my closet.

I know that the covers I wrap so tightly around me

Offer no protection from what time has brought (me):

The drowning of the light by the darkness.

I bury my head in the night and dream of the return of tomorrow.

© Igor Goldkind, September 25th, 2017

Diamond Rain

Caught unawares in a diamond rain shaking with cold

How did fate suddenly get so quick and immediate?

When did I step off into myself,

And begin to orbit time?

The vantage point that surrounds us

Is not just this moment,

But every moment you and I have ever or will ever live.

A handful of gems lie scattered like dust at my feet.

Each crystal reflecting every other facet of being.

Each stone weighs down heavy on my stomach.

Forced downward by the sheer gravity of events.

When I step out of myself,

I am no longer there.

Or rather I am here,

Just not in this world

In another that is merely reflection.

2 mirrors facing each other

A rag collects the dust between dirty faces.

This masquerade of illusions; bodies blocking light.

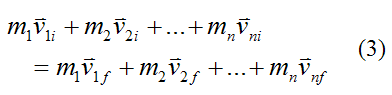

p=m√

This moment is dead.![]()

But your life is momentum.

It’s the only life you know:

Everywhere you look

Is exactly where you’ll go.

(Paying attention like a fine,

Sniffing out the muddied footprints of the divine.)

This ticket that you’re riding,

Fare-less and Free,

Is merely the impetus of your Desire

Conserved, unaffectedly

By any other force or sway

Upon your singular trajectory through time.

For Tatiana Iosifovna Doubro who is ejected from planes and recites Pushkin by heart as she is flies through space.

Psychoanalysis and Psychology at their best are not sciences at all, they are merely methodical enquiries into the nature of the mind (although the current bias towards quantifiable and numerical conclusions might make one think otherwise). They are a result of mystical enquiries into the nature of the mind and how it shapes our most intimate and fundamental perceptions of the world we live in; the space in time we briefly occupy before dying. Medicine is yet another example of a supposed science that in fact is based on a field of knowledge that predates scientific methodology.

Psychoanalysis and Psychology at their best are not sciences at all, they are merely methodical enquiries into the nature of the mind (although the current bias towards quantifiable and numerical conclusions might make one think otherwise). They are a result of mystical enquiries into the nature of the mind and how it shapes our most intimate and fundamental perceptions of the world we live in; the space in time we briefly occupy before dying. Medicine is yet another example of a supposed science that in fact is based on a field of knowledge that predates scientific methodology.

I am nurturing in the sense that I get a kick out of helping my friends, or even those I don’t know, sometimes just with honest conversation.

I am nurturing in the sense that I get a kick out of helping my friends, or even those I don’t know, sometimes just with honest conversation.

Coming Soon!

Share & Disseminate This With Your Friends

January 9, 2021 | Categories: art, book launch, books, comments about poetry, digital insurgency, Existentialism, Faith, Healing, literature, Meaning of Existence, Meditations, mental health, Mindfulness, new poetry, Paper Bag, physics, poetry, Poetry as therapy, Poetry Therapy, politics, Self-Therapy, spoken word, story-telling, Suicide, Therapy, Zen | Tags: Democracy, Donald Trump, philosophy, poetry, Poetry Therapy, Therapy | Leave a comment